By Ahmad Jenkins

“ It’s trouble that makes the monkey chew hot peppers” – African proverb

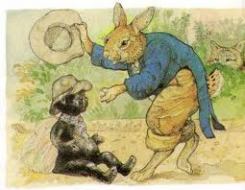

My first introduction with the character Br’er Rabbit was in the 5th grade when I read ‘Granny cutta the cord’. I loved the way Br’er Rabbit escaped getting eaten, but also saved his granny. These stories were always filled with impossible situations where Br’er Rabbit always managed to find a means of escape.

From that point I fell in love with these tales as I’m sure many other African Americans did in their childhood. What I loved about those tales was the unique way Br’er Rabbit over came his foes, and that was through tricking them in humorous ways. As entertaining as these tales were, they also have a historical significance within the development of African American literature.

Br’er Rabbit and American Slavery

What is interesting is that during the time the Br’er Rabbit tales were being told by slave storytellers, they weren’t just tales to entertain children; rather these stories were actually serious criticisms of the society in which slaves lived in. Forced to endure illiteracy, harsh working conditions, and treatment. Slaves had very few resources to preserve any form of culture outside of slavery.

If they protested it brought on harsh penalties, so in telling these tales slaves were able to preserve a part of their culture; as well as seriously critique the human injustice they faced. We find in the character of Br’er Rabbit a quintessential trickster who by using wits over brawn, fooling of authority figures, and his bending of social norms in a way reflected the over all behavior of slaves towards those that ‘owned’ them. According to the historian Lawrence W. Levine:

“ The records left by nineteenth century observers of slavery and by slave owners themselves indicate that a significant number of slaves lied, cheated, stole, feigned illness, pretended to misunderstand orders given to them, placed rocks in their cotton basket to meet quota. They also broke their tools, destroyed property, mutilated themselves; and mistreated livestock so that the slave owners had to use the less efficient mule, rather than horses because the latter could withstand harsh treatment of the slaves.”.

We can see a very sharp similarity between the trickery of Br’er Rabbit, and the arrogance of slaves during the American slave era.

The Emergence of African American Literature

During the 1880’s American Folklore society collectors found a series of tales that did not disguise the actions between black slaves and those that held them in bondage. They discovered what is called John and Old master tales.

In these tales ‘John’, representative of enslaved blacks manages to get the best of ‘Old Master’ in almost every situation in which they are pitted against each other. It’s a world where the weak, and the witty always triumph over the powerful, and the presumed intellectually superior. Robert Roosevelt, the uncle of Theodore Roosevelt, began collecting the tales of Br’er Rabbit. The stories at that time did not become popular among people outside of the black community. It wasn’t until authors, such as Joel Chandler Harris, Alcee Fortier, and Enid Blyton in the late 19th century compiled these stories independently popularizing them for the mainstream audience.

In 1899, Charles Waddell Chesnut wrote and published “ The Conjure Woman” based upon Harris’s Uncle Remus tales. Contemporary with Chestnut was Paul Lawrence Dunbar, the poet who wrote “An Ante Bellum Sermon”, and “ Accountability”. Both Dunbar and Chestnut wrote at a time when creativity amongst blacks was strictly prohibited, they found an outlet using trickster paradigms. From there, we see African American authors such as John Oliver Killen “The Cotillion or One Good Bull is Half the Herd”, and Langston Hughes’s, “ Who’s Passing for Who?”

The Uncle Remus tales of Br’er Rabbit sparked a unique way for African Americans to develop our own literary culture that not only entertained us, but also allowed our self-expression to overcome censure, and continues to inspire modern day African American writers and authors to carry on that tradition.

Reblogged this on Stranger on the road and commented:

My favorite article, that I’ve written so far.

LikeLike